In public health records, gastrointestinal problems are among the most common causes of consultation in the general practice. But one thing is having a transient gastrointestinal symptom.

In comparison, it is very different to experience chronic gastrointestinal problems. In the first case scenario, patients can get a given medication and feel better.

But when you have to live with digestive issues, things start to get a little bit messier. Maldigestion problems, food intolerance, and others can change your life dramatically.

That is why, in this article, we are going to take a quick look at exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. It is also known as EPI.

We’re going to find out what it is and the symptoms patients usually report. We’re also taking a look at the diagnostic process and the correct management of this problem.

What is EPI?

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is a chronic health problem. That means patients experience symptoms over a long course. As it implies, EPI has to do with the function of the pancreas as a gland.

The pancreas has a twofold function as a gland. It works as an endocrine gland or as an exocrine gland. There’s an endocrine gland, the pancreas synthesize and secrete insulin and glucagon.

These two hormones regulate the metabolism of carbohydrates. Insulin is emitted to the bloodstream when blood levels of glucose go up. Glucagon is secreted when blood levels of glucose go down.

But, as an exocrine gland, the pancreas synthesizes and secretes pancreatic juice. This substance is released into the duodenum, the first portion of the small intestine. The pancreatic juice is synthesized by the pancreatic acinar cells. They store the pancreatic juice and secrete it in response to the parasympathetic nervous system.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency features an inability of the pancreas to function as an exocrine gland. The secretion of pancreatic juice into the duodenum becomes impaired and there is a reduction of digestive enzymes.

The pancreatic juice has pancreatic lipases, proteases, and amylases. Thus, patients may not digest proteins, fats, starch, and maltose properly (1).

Fortunately, there are other enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract. They contribute to the breakdown of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

However, the pancreatic juice has 90% of the lipases for fat digestion. That’s why patients have more profound problems to digest fats compared to other nutrients (2).

Get Your FREE Diabetes Diet Plan

- 15 foods to naturally lower blood sugar levels

- 3 day sample meal plan

- Designed exclusively by our nutritionist

What causes EPI?

Various environmental health causes may lead to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Others are not dependent on the environment but on the health condition of the patient. We can divide the causes into pancreatic and nonpancreatic (3):

Pancreatic causes include chronic and acute pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis. It also happens when the pancreatic duct is obstructed. And patients with diabetes may also develop an EPI.

Nonpancreatic causes usually include gastrointestinal problems. Crohn’s disease and celiac disease more commonly cause it. It may also be an unexpected side effect of a surgical procedure.

- Chronic pancreatitis: When inflammation remains for a long time, the pancreatic tissue suffers the consequence. In some cases, chronic pancreatitis leads to necrosis of the pancreatic tissue. The affected tissue becomes fibrotic and loses its functions.

- Acute pancreatitis: A significant number of patients with acute pancreatitis have transient EPI., Especially those with autoimmune pancreatitis. Upon admission, they usually have characteristic symptoms. And sometimes, the condition remains after discharge. Even patients with mild acute pancreatitis may develop the disease (4).

- Cystic fibrosis: This is a chronic disease that affects the secretions of the body. That includes body sweat, respiratory secretions, and other exocrine glands. The secretion of the pancreas loses its fluidity, and the ducts become plugged. In some cases, the process may even lead to the autodigestion of the pancreatic tissue.

- Pancreatic duct obstruction: Similar to cystic fibrosis, an obstruction due to any other cause may lead to EPI.

- Diabetes Mellitus: In patients with type 2 diabetes, high insulin levels affect the acinar cells. Such a high level of insulin activates cellular stress and may lead to an EPI (5).

- Celiac disease: It is an inflammatory bowel disease. In many cases of celiac disease unresponsive to the medical treatment, it is because the patient has an EPI as well.

- Crohn’s disease: The autoantibodies in Crohn’s disease may also affect the pancreas. When it does, the exocrine function of the gland is often impaired.

- Surgical procedures: Changes in the pancreas or related abdominal organs may lead to dysfunction. For example, after pancreatic cancer resection. Anything that changes the stimulation or volume of pancreatic parenchyma may cause EPI (6).

- Congenital causes: Other rare causes include the Shwachman-diamond syndrome. This syndrome features skeletal and bone marrow abnormalities and EPI.

What are the symptoms of EPI?

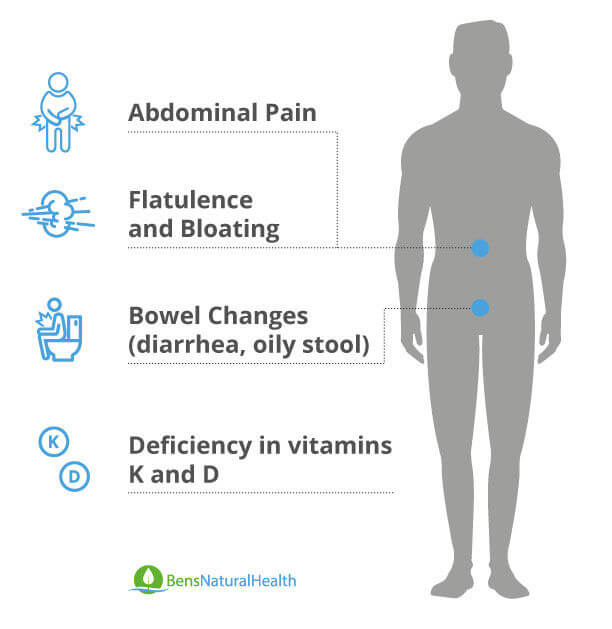

Naturally, a problem with digestive enzymes causes absorption problems. In the case of EPI, the main absorption problem deals with dietary fat. We will also have nutritional problems, diarrhea, and other symptoms listed below (7):

- Steatorrhea: Instead of being absorbed, fat particles stay in the gut. They increase the bulk of the stools as patients eliminate them in their feces. This deposition of fatty acids in the stool is called steatorrhea.

Recognizing steatorrhea is not difficult. It looks like pale and bulky stools. They are often foul-smelling, and you will find them floating with oily droplets in the toilet. When they are abundant, it may be even difficult to flush because the fatty droplets always stay on top.

- Diarrhea: As patients eliminate fat in the stool, there’s a high chance they will get diarrhea, too. That’s especially the case in people who eat a high-fat diet. Instead of being absorbed, fat stays in the gut and drags water along, increasing bowel movements.

Thus, we are talking about watery diarrhea that may also weep out the gut microbiota. The patient may also have severe nutritional problems in some cases.

- Weight loss: Another common consequence of the absorption problem is weight loss. It is an unintended weight loss that goes beyond any therapeutic measure. Weight loss is often accompanied by severe nutritional problems, as mentioned above.

However, many individuals compensate for their low-calorie consumption by eating more. Keep in mind that some patients with EPI also have Crohn’s disease or celiac disease. This may be an additional underlying cause of weight loss.

- Abdominal gas: patients with EPI may also develop abdominal distention and gas. Unabsorbed food substances are fermented by bacteria and release methane and hydrogen. Thus, they also report flatulence and abdominal pain.

Who is at risk of developing EPI?

As noted above, patients with a high risk of developing EPI will be:

- Patients with celiac disease

- Patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease

- Patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis

- Patients with an advanced and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes

Anyone who underwent surgical procedures in the pancreas or adjacent organs

All of the above are pancreatic or nonpancreatic causes that may lead to EPI. Out of these, the highest risk of EPI comes with chronic pancreatitis. In these patients, EPI is a consequence of their chronic disease after 5 to 10 years.

According to the epidemiology, most patients with cystic fibrosis will also develop EPI. Another group with a very high risk is pancreatic surgery patients. However, the proportion of patients with EPI is variable (7).

What are the complications of EPI?

Complications of EPI arise when there are not sufficient measures or patients neglect their symptoms.

In such cases, the problem goes on and becomes aggravated as it does. The majority of complications are associated with nutritional deficiencies. They are as follows (7):

- Edema: In cases of chronic disease, patients may also have malabsorption of proteins. In these cases, they have fluid accumulation in the body, clinically known as edema. In very severe cases, patients may develop an extensive collection of abdominal edema, called ascites.

- Anemia: We can have a vitamin B12 deficiency or iron deficiency in EPI. In both cases, patients reduce their blood count, and this is called anemia. A common symptom of anemia is fatigue or tiredness.

- Bleeding problems: In cases of vitamin K deficiency, patients may also have bleeding episodes. They may get sudden and unexplained bruises, called ecchymosis. In other cases, they have gastrointestinal bleeding, as in melena. Or bleeding through the urinary tract in hematuria.

- Other nutrient deficiency problems: Depending on the nutrient, patients may have other pathologies. Among older adults, vitamin D deficiency may be common. It results in osteopenia and pathologic fractures. We may also have muscle weakness due to vitamin B deficiency. Or an electrolyte disturbance causing tetany and other neurologic symptoms.

Diagnosing EPI

One of the most alarming problems of EPI is how neglected it is, even among clinicians. This condition is usually not considered among the differential diagnoses.

Patients come with a nutrient deficiency, and only a few doctors rule out an EPI. Thus, these patients are routinely undiagnosed and routinely untreated. But is it challenging to diagnose EPI?

We have many tests, but not all of them are specific for EPI. Instead, doctors need to rely on clinical signs and symptoms. It is also important to evaluate their risk factors.

If a patient belongs to a high-risk group and starts developing symptoms, we should include EPI in the diagnostic list.

However, the signs and symptoms are common to those found in other gastrointestinal diseases. Thus a clinical suspicion is very important to guide the diagnosis.

We can divide tests for patients with EPI in two groups. In the first group, we have tests to diagnose EPI. In the second group, we will see tests that will help us diagnose EPI-related conditions. Sometimes using both should be a part of the initial diagnosis.

The most appropriate tests to diagnose EPI are as follows:

- Stool chymotrypsin and elastase: In the feces, we can measure levels of exocrine pancreatic enzymes. Among them, the most useful are chymotrypsin and fecal pancreatic elastase. These pancreatic enzymes break down proteins. They are only synthesized in the pancreas and help us diagnose EPI.

- Fat absorption test: It is usually one of the first tests to be ordered. It can be performed in a sample or a 72-hour fecal collection. The latter is more reliable and recommended to diagnose EPI. For preparation, patients need to consume 80 to 100 grams of fat a day. This test gives a percentage of fat absorption, and 90% is considered normal (8).

- D-xylose test: This substance is absorbed in the intestines and excreted in the urine. In cases of celiac disease and intestinal bacterial overgrowth, it is not adequately absorbed. Thus, urine levels will be lower. This test is used to rule out diseases associated with the intestinal mucosa. It should not be recommended for patients with chronic kidney disease.

- Direct pancreatic function tests: When there’s a high suspicion of EPI, doctors perform this test via endoscopy. During the endoscopy, the pancreas is directly stimulated. Then secretin or cholecystokinin levels are measured. Sometimes both exams are recommended, and sometimes only one of them is enough.

- Indirect pancreatic function tests: They are useful as a screening test. This test combines a fecal fat quantification and stool chymotrypsin and elastase levels. These tests are more accurate in patients with chronic pancreatitis (9)

Moreover, these tests help us determine the causes or consequences of EPI in the patient:

- Blood tests: In a blood test, we can evaluate anemia and understand its cause. It is also possible to measure vitamin B12, folate, and iron levels. In vitamin K deficiency, the prothrombin time is prolonged. And we can even evaluate the risk of patients with chronic pancreatitis.

To do that, we can use magnesium, albumin, and prealbumin levels. These nutritional markers are useful to determine the probability of EPI. Other blood tests may help us rule out a celiac sprue (anti endomysial antibodies) or a IgA deficiency (serum IgA levels) (10).

- Schilling test: It is a special test designed to evaluate the intrinsic factor. The stomach secretes this substance. Thus, it helps us differentiate the cause of vitamin B12 malabsorption.

- Abdominal imaging: It is commonly used in an EPI setting to diagnose acute or chronic pancreatitis as the main trigger of the condition.

Prevention

Preventing EPI is usually achieved by early treatment of pancreatitis. However, it is sometimes difficult to avoid this additional health problem.

For example, in cases of cystic fibrosis, this complication is very difficult to avoid. Thus, what we have to do is preventing the symptoms.

We can do that by adopting a few lifestyle modifications and through vitamin supplementation.

The most important lifestyle recommendations to prevent or minimize the symptoms of EPI are as follows:

- Avoiding fatty foods with a low-fat diet

- Limiting or quitting alcohol intake

- Quitting smoking

- Consuming a balanced diet with all of the nutrients

- Following other dietary recommendations if the doctor prescribed a gluten-free diet or similar

Among the most important vitamins to prevent deficiency, we have the following:

- Vitamin A

- Vitamin D

- Vitamin E

They are fat-soluble vitamins, and the most commonly affected by a deficiency in EPI.

Treatment/ management

Treatment should include medications and the recommendations listed in the section above. The therapeutic mainstay is pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. The goal is to normalize enzyme levels and correct the absorption problems. In many cases, any sign of nutritional deficiency will also go away. However, patients with a secondary deficiency should also get supplemented.

The combination of steatorrhea and significant weight loss is usually enough to start treatment. According to clinical trials, it should be done with high doses of enzymes, and they should have an enteric coat (11). All enzymes should be administered along with foods, and there are many to choose from. All of them contain a proportion of three pancreatic enzymes. They are amylase, protease, and lipase.

If they do not have an enteric coat, they should be administered with a proton pump inhibitor. The goal is to protect the oral pancreatic enzymes from the gastric acid. Treatment is not as simple as choosing enzyme products and taking it with foods.

Correct treatment should be based on the content of lipases and the symptoms of the patient. Low doses can cause therapeutic failure. Large doses may result in other problems, such as a colonic stricture. Thus, they should be prescribed by your healthcare provider, and patients should follow strict recommendations.

Conclusion

EPI is short for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. It is usually secondary to pancreas disease, cystic fibrosis, or pancreatic surgery. In this ailment, the pancreas no longer secretes pancreatic enzymes. Thus, the patient develops absorption problems and may have nutrient deficiencies.

This condition is highly underdiagnosed and undertreated. It is very similar to other gastrointestinal conditions, and commonly mistaken.

However, there are various tests to evaluate pancreatic function. We can do it directly or indirectly. There are also easier tests we can do to screen high-risk patients for EPI.

The treatment for these patients is not complicated. Their symptoms are usually relieved after using exogenous pancreatic enzyme supplements. Enzyme supplementation should be administered along with the food. However, the dosage should take into consideration the concentration of lipase, and healthcare professionals should prescribe it.

Explore More