- What is Testosterone?

- Normal testosterone levels by age group

- How do testosterone levels affect men’s health?

- Is there a link between testosterone and prostate cancer?

- University of Vienna – 2000 – 2001

- The role of testosterone therapy for prostate cancer

- Testosterone therapy in patients with treated prostate cancer:

- Testosterone therapy in patients with untreated prostate cancer:

- Conclusion

- Source

Testosterone and prostate cancer are both subjects of interest for many men

Some individuals seek testosterone sources for various reasons, including potential impacts on physique. It’s crucial to understand the complexities involved.

While testosterone plays a role in sexual health, claiming it universally improves various health problems may be misleading. Individual responses vary.

Prostate cancer is a prevalent concern for older men, often causing stress and worry. However, its development is influenced by various factors.

While aging may impact testosterone levels and prostate health in some individuals, it’s essential to recognize the variability in these experiences.

Exploring the potential association between prostate health and testosterone levels requires a nuanced examination of various factors.

Testosterone plays diverse roles in various tissues, prompting the question of how its levels specifically affect the human prostate and its intricate functions.

Understanding the potential risks of prostate cancer associated with testosterone therapy is a complex consideration that requires thorough evaluation and consultation.

Get Your FREE PSA Lowering Diet Plan!

- Naturally lower PSA levels

- Reduce nighttime trips to the bathroom

- Enjoy better bladder control and urine flow

What is Testosterone?

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone, a steroid synthesized by the testes with multifaceted functions in the body.

There are various types of steroids, and testosterone is classified as an anabolic steroid, crucial for the development of primary sexual characteristics in men.

Testosterone plays a key role in initiating changes such as alterations in tone of voice, the growth of body hair, and the increase of muscle mass.

This hormone interacts with various tissues and cells in the body. Both men and women produce testosterone as it is synthesized not only in the testes (1).

Low testosterone levels in men may have effects similar to low levels of estrogen in women. Occasionally, men may experience mood swings, hot flushes, and other issues related to sexual function (2)

The physiological effects of testosterone commence around puberty when synthesis increases in the testicles. These effects vary depending on the specific tissues involved.

In the prostate, testosterone stimulates the secretion of fluids, contributing to semen volume and increasing the size of the gland during early puberty.

However, the effects of testosterone in prostate cancer remain controversial, as you will see in this article (3).

Normal testosterone levels by age group

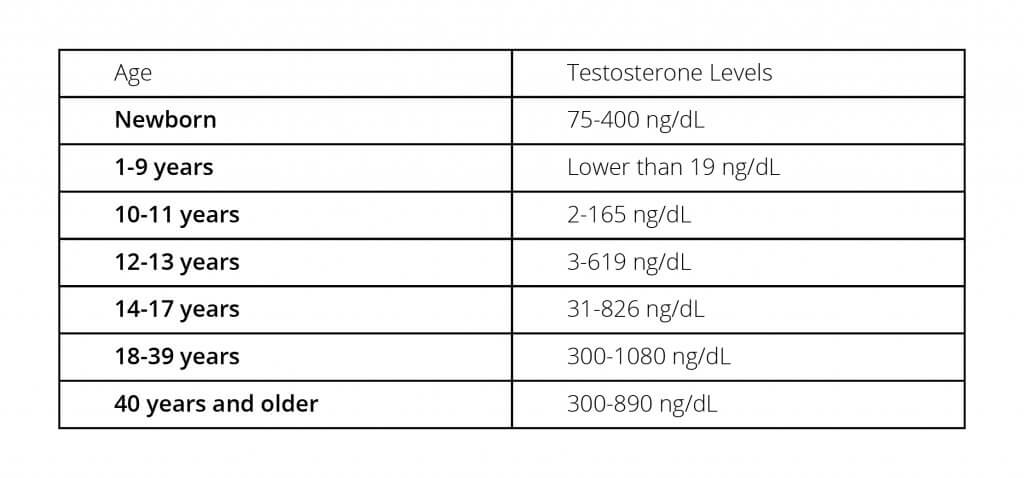

Testosterone levels go up and down, and there are normal values for each stage. As a consequence, men change during childhood, puberty, adolescence, adulthood. As an older adult, and we can relate these changes with their testosterone levels.

We can create a basic chart of healthy testosterone levels by age group, and it would look like this:

Many children may begin puberty changes around 10-13 years old, and the typical onset of puberty is expected before 17 years old. During this period, there is an increase in typical values of children’s testosterone levels.

After 18 years old, average testosterone values are generally expected to be higher than 300 ng/dL, continuing into adulthood and senior years. However, individual variations exist.

However, it’s generally observed that testosterone levels tend to decline after the age of 40. (4)

How do testosterone levels affect men’s health?

All of these changes in testosterone levels throughout the lifetime affect men’s behavior and health.

During puberty and adolescence, increasing levels of testosterone are generally associated with an interest in sex and high libido. (5).

After that, adults and older adults, especially after the age of 40, experience a progressive decrease in their testosterone levels, which is commonly attributed to for up to 2% every single year.

This has a mounting effect in our circulating levels of testosterone. By our seventh decade, it is expected that men have 35% lower levels of testosterone compared to their youth.

When their levels reach the lower threshold, they are at risk of late-onset hypogonadism. Symptoms that may be experienced include: (6,7).

- loss of libido.

- obesity.

- and a worrying predisposition to certain diseases (6,7).

In these cases, testosterone replacement therapy is recommended to improve the effects of low testosterone. The symptoms of low testosterone levels are as follows (8):

- An impaired sexual function: Testosterone is the sex hormone. As such, it is essential for sexual behavior and reproduction. Men with low testosterone may experience various forms of sexual dysfunction, including low libido, erectile dysfunction, and infertility.

- Psychologic and cognitive changes: They include difficulty to recall and learn new data. Men with low testosterone levels would also display low energy levels and suffer from depression, irritability, mood swings, and other symptoms.

- Metabolic disease: Other hormones would start to become dysfunctional as a result of low testosterone levels. This can lead to insulin resistance, high levels of fatty acids in the blood, diabetes, and other health problems.

- Musculoskeletal problems: Low testosterone levels are associated with sarcopenia (a significant reduction of muscle mass) and osteoporosis (a problem with bone mineralization) in men.

As their testosterone levels decrease, men would also increase their risk of prostate disease, including benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Thus, is there an association between this hormone and prostate health?

Is there a link between testosterone and prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is a significant concern, particularly for men experiencing lower urinary tract symptoms and those with a family history of the disease.

There has been a historical belief that testosterone levels increase the risk of prostate cancer in men, but is it true?

This belief originated in 1941 when Huggins and Hodges published their study, evaluating the effects of castration, estrogen, and androgen injections on prostate cancer. They concluded that prostate cancer progression and growth are directly associated with androgenic activity (9).

However, almost 80 years later, subsequent research has revealed a more nuanced understanding, particularly when evaluating testosterone replacement therapy (10).

So, what is behind this discrepancy?

The initial androgen hypothesis by Huggins and Hodges remains influential in treating prostate cancer. However, it’s important to note that hormone therapy can have various side effects.

In vitro, testosterone has been observed to contribute to the replication and tumor growth in prostate cancer cells. When deprived of testosterone, cancer cells may undergo apoptosis (cell death).

However, recent evidence has provided additional insights into the complexities of prostate cancer. For instance, different lines of prostate cancer may react differently, with some becoming resistant to androgen deprivation and persisting (11).

Moreover, it’s crucial to note that these are in vitro studies conducted under ideal lab conditions, which may not fully replicate the complexity of living human conditions. In reality, serum testosterone levels (those found in the blood) may not accurately reflect intraprostatic levels

In other words, patients who receive testosterone therapy may experience a significant increase in free testosterone in the blood. However, it’s noteworthy that testosterone levels in prostate tissue may not consistently change significantly across all patients (12).

Adding to the complexity, it appears that cancer cells and their surrounding tissue create an environment where androgens are synthesized. This process may play a role in the intricate dynamics of prostate cancer, regardless of serum testosterone levels.

We can take a look at a study by Miyoshi et al. The researchers evaluated the prostatic environment and testosterone levels in prostate biopsies from 196 prostate cancer patients.

They found that higher levels of testosterone correlated with more advanced or aggressive prostate cancer with a higher Gleason score. However, in evaluating the benign and malignant sections of each biopsy, they observed that testosterone levels did not consistently differ between the two (13).

University of Vienna – 2000 – 2001

There are two studies of note between 2000-2001, both completed at the University of Vienna. The first, in 2000, had a small group of men (5 in total) with prostate cancer whose level of testosterone was lower than those in the healthy control group.

However, they also found that DHEA (the other major androgen) did not show a negative correlation with cancer. The below quote from the study says it all;

“These data are confirmed by the present study; it can be concluded that DHEA or DHEA-S serum concentrations represent no risk factor for PC [prostate cancer] development.”

The men in the study group with the highest Gleason scores had an average testosterone level of 2.8 ng/ml, while those with the lowest Gleason scores had levels averaging 4.10 ng/ml.

Again, this study mentioned DHEA and confirmed DHEA-S levels averaged the same in both groups, finding that DHEA is not a contributor to cancer.

The role of testosterone therapy for prostate cancer

Treatment for prostate cancer may include androgen deprivation therapy in cases of metastasis.

Androgen therapy works by reducing androgen synthesis and creating an environment that will force prostate cancer cells to undergo apoptosis.

However, this is not a standalone therapy and should be applied along with radiation therapy and other choices.

This is because malignant cells without testosterone find an alternative way to stimulate prostate cancer growth and ultimately become resistant and independent of androgens (14).

This way, they will be more sensitive to any change in testosterone levels. Even minimal concentrations of this hormone would trigger growth.

A topic we should cover is whether or not to use testosterone replacement therapy.

The answer will widely depend on the stage of prostate cancer and any previous treatments the patient has undergone:

Testosterone therapy in patients with treated prostate cancer:

According to many clinical trials, prostate cancer patients who have been surgically treated (radical prostatectomy) and those who underwent radiotherapy are safe to receive testosterone replacement therapy.

This type of patient will not have recurrence of cancer but may have a minor increase in PSA levels (15,16).

However, patients with metastatic cancer who received androgen deprivation therapy should be assessed carefully.

This therapy has changed the way androgen receptors are expressed in the prostatic tissue, and these patients may have rapid progression of cancer as a side effect (17).

Testosterone therapy in patients with untreated prostate cancer:

In these patients, there’s controversy about whether testosterone replacement therapy is appropriate.

According to a scientific review, patients who are under active surveillance of prostate cancer should not start testosterone replacement therapy (18).

However, other studies have found that men with untreated cancer who began testosterone replacement therapy had the same progression rates after 3 years than those not given testosterone (19).

According to a study published in the journal The Aging Male, it appears that not treating testosterone deficiency might be one of many risk factors we can prevent in men with intact prostate health.

The study compared data from 776 hypogonadal men, among which 400 men underwent testosterone replacement therapy, and 376 did not receive any intervention.

After 7 years, 26 cases of cancer were recorded among those who did not receive replacement therapy against 9 cases in the treatment group.

Thus, unstable and low serum testosterone levels are associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer. Treating testosterone deficiency at a younger age may reduce the incidence of prostate cancer as patients grow older (20).

Conclusion

There is definitely no simple way to address the issue of testosterone and prostate cancer.

It is one of the most complex and controversial topics in urology and oncology. For the past eighty years, the idea that testosterone causes prostate cancer has pervaded the conventional medicine approach to treating prostate disease.

But get this: the fall in testosterone as men age almost exactly parrels the rise in the incidence of BPH, prostatitis and prostate cancer. If testosterone alone was the cause of cancer, then 18-year old men- who have the highest levels of testosterone-would suffer from prostate cancer. Something doesn’t quite line up with this high testosterone dogma.

Low levels of testosterone in men are not related to a lower chance of prostate cancer but the contrary.

We can explain this apparent contradiction by summarizing the following points:

- Testosterone levels in the blood are not the same and will not predict testosterone levels in the prostatic tissue.

- Prostate cancer cells and their surrounding tissue are capable of creating an androgen biosynthesis environment of their own.

- Prostate cancer therapy considers androgen deprivation therapy, but not in every patient, and always in association with another treatment.

- There are many cancer cell lines. Some of them will die under androgen deprivation, while others will become resistant to the therapy.

- It is possible to recommend testosterone replacement therapy in patients with prostate cancer and late-onset hypogonadism. However, every case should be assessed individually.

Although treatment in many prostate cancer patients is specifically designed to reduce testosterone levels, there are many studies available that show a fall in testosterone in men actually almost parallels the rise in BPH, prostatitis and prostate cancer, which throws up some pretty interesting questions.