- Types of Prostate Cancer

- What are the symptoms of Prostate Cancer?

- What is a Gleason Score?

- How common is Prostate Cancer?

- What causes Prostate Cancer?

- Can you feel if you have Prostate Cancer?

- What's new in Prostate Cancer diagnostics?

- Are there any natural treatments that support prostate cancer?

- What is Active Surveillance?

- The best protocols for Active Surveillance

- Our Natural & Non-Invasive Prostate Biopsy Alternative

- Can I survive Prostate Cancer?

- Conclusion

- Source

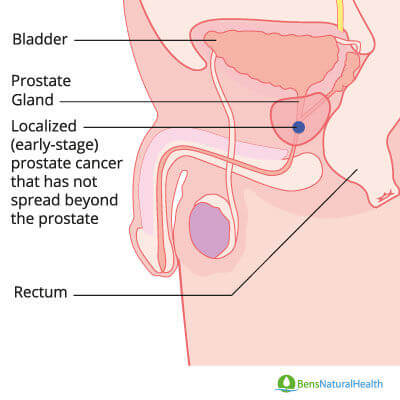

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate gland, which is located between the bladder and the penis.

The prostate gland surrounds the urethra, which is the tube that runs from your bladder to the end of your penis and allows urine to exit your body.

The prostate gland secretes various enzymes and proteins that ensure that sperm can move and flow freely.

It is an essential organ in male reproductive health.

Prostate cancer is typically formed of adenocarcinoma cells; these are cancerous cells that develop from glandular tissue.

Types of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer can be localized to the prostate or metastatic.

Localized Prostate Cancer

Localized prostate cancer: means that the tumor is confined to the prostate gland.

Approximately 90% of all prostate cancers diagnosed in the USA are localized at the time of diagnosis.

Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Metastatic cancer: this is when prostate cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as organs, bones, and lymph nodes.

These tend to be far more aggressive and dangerous types of prostate cancer.

Cancers are classified according to which organ they originate in.

So even if the prostate cancer spreads to somewhere else in the body, e.g., the lungs or bones, it remains prostate cancer (it does not become bone or lung cancer).

90% of prostate cancers that are localized are more likely to be slow-growing cancers.

On average, the period in which you have prostate cancer before it is detectable by most diagnostic methods is between 7-14 years.

Prostate cancers rarely change forms, meaning slow-growing prostate cancers will usually remain slow-growing.

The editor of an annual report on prostate disease from Harvard Medical School, Dr.Garnick, stated that the “[prostate cancers] that are low-grade and indolent are unlikely to cause problems in a man’s lifetime,”

Some men with low-grade, slow-growing prostate cancers may experience a non-life-threatening course, although medical monitoring and individual risk assessments are crucial.

What are the symptoms of Prostate Cancer?

While the PSA test is not definitive, a sudden change in the PSA level can be indicative of prostate cancer.

If your PSA begins to climb rapidly and approaches or increases over 10 mg/mL, it is likely that you have some cancerous cells in your prostate gland.

There are other diagnostic scans you can have if you are concerned about prostate cancer. You can read about them here.

While prostate cancer is often asymptomatic, it’s important to be aware of potential early warning signs that may warrant further medical evaluation.

However, these can also be warning signs of BPH, a prostate, or bladder infection.

So if you do have any of these symptoms, don’t panic, but do talk to your doctor.

- Painful urination.

- Difficulty urinating, or weak flow.

- Nighttime urination (nocturia).

- Loss of bladder control.

- Blood in your urine (hematuria).

- Blood in your semen.

- Painful ejaculation.

- Persistent pain that feels like it originates in the bones.

- Increased frequency or easy of fractures and breaks.

- Swelling in your legs and pelvic area.

- Numbness in the feet, legs, and hips.

If prostate cancer has already metastasized to the bones and spine, it can result in additional symptoms.

Symptoms of late-stage cancer include painful ejaculation, persistent pain that feels like it originates in the bones, increased frequency of fractures and breaks, swelling in your legs and pelvic area, numbness in the feet, legs, and hips.

Again, it’s important to note that these symptoms can also be caused by a variety of conditions, and the presence of any or all of them guarantees the presence of cancer.

What is a Gleason Score?

Named after its creator, Dr. Donald Gleason, the Gleason scoring system was developed at a VA hospital in the 1960s. It was quickly adopted all over the world as an effective predictor of the pace of prostate cancer growth.

It is now the standard prostate cancer screening used across the world.

The Gleason score is a measurement that is given to indicate the aggressiveness of prostate cancer tumors.

“Aggressiveness” being the medical term used to describe the likelihood of cancer metastasizing.

The higher the Gleason score, the greater the risk of your prostate cancer spreading to other organs, bones, or lymph nodes.

The Gleason score is a valuable tool for evaluating the aggressiveness of prostate cancer but should be used in combination with PSA levels and rectal examination for accurate screening.

If prostate cancer does spread to nearby lymph nodes, then it can become a more dangerous and life-threatening disease.

The way a Gleason score works is actually fairly simple. Different patterns of prostate cancer cell growth are ranked from 1 to 5.

When your pathologist checks your biopsy samples, they examine your prostate cells under the microscope and will look at the different patterns. The patterns of prostate cancer cells show how quickly and aggressively they are growing.

The lab will then choose the two most commonly appearing patterns and give you a score. The score might look something like this 3+4 = 7.

The first number indicates the most common pattern in all the samples. The second is the second most common pattern. When these two scores are added together, the total is called the Gleason score.

In this example, the two most commonly appearing patterns are Gleason 3 and Gleason 4, which means that the tumor is primarily made up of cells that fit pattern 3 and, to a lesser extent, cells that match pattern 4. If this is your score, it will be written As Gleason 7 (3+4) or Gleason Score 3+4 = 7.

The order of the numbers is, therefore, very important since the first score is the most common pattern of prostate cancer cells.

This means that a Gleason score 4+3=7 tumor is thought to be more aggressive and fast-growing than a 3+4=7 tumor.

It is worth noting that patterns 1 and 2 are rarely seen, either because they are hard to distinguish from healthy cells, or because biopsies are seldom conducted on men who would have such low PSA levels and would probably be asymptomatic.

Because patterns 1 and 2 are rarely seen, the lowest Gleason score of cancer normally found on a prostate biopsy is 6 and because the patterns are all scored between 1 and 5, the highest a Gleason can be is 10.

The higher your Gleason score, the greater the likelihood of your cancer spreading outside the prostate.

There are several problems with the Gleason score system.

Firstly accuracy, in approximately 20% of cases, the score will be lower than your actual score since the biopsy misses a higher grade area of cancer.

The pathologist can overestimate the aggressiveness of a tumor, and end up with a Gleason score that is higher than it should be.

The second problem is the potential for cancer cells to be spread by the procedure.

Some research has raised concerns that the act of inserting and withdrawing the needles into a prostate cancer that is contained within the prostate gland, could risk spreading cancer. This could happen as the needle is removed.

Prostate Biopsy

Finally, some men may be concerned with the fact that a biopsy is a surgical treatment.

However, a biopsy is normally an outpatient procedure done under local anesthetic. And the normal side effects of a biopsy are relatively mild and normally only require a short period of recovery.

Normal side effects of a biopsy can include:

- Bruising around the biopsy site.

- Blood in your pee.

- Infection.

- Short term trouble urinating.

Some cases of biopsy would give out additional side effects, such as chronic pain and bleeding of the urinary tract.

Thus, biopsy should be performed after carefully evaluating PSA values, rectal examinations, and the medical history of the patient to prevent false positives and inappropriate use of biopsy in patients who do not require this procedure.

How common is Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer is one of the most common types of cancer that can affect men; only skin cancer is more common.

The median age for being diagnosed with prostate cancer is 66, with 60% of all new diagnoses of prostate cancer being given to men over 65 years old.

Prostate cancer is not just the second most common type of cancer; it is the second most common cancer death for American men.

Approximately 1 in 41 American men will die of prostate cancer. These odds are the same for British and European men.

Get Your FREE PSA Lowering Diet Plan!

- Naturally lower PSA levels

- Reduce nighttime trips to the bathroom

- Enjoy better bladder control and urine flow

What causes Prostate Cancer?

The exact causes of prostate cancer are still unknown though we have identified some key risk factors that can increase your odds of developing prostate cancer.

There is a strong correlation between your age and your risk of developing prostate cancer.

As discussed above, 60% of all new diagnoses of prostate cancer are given to 65-year-old men or older.

After turning 50 years, prostate cells are more likely to increase in number and size.

After 65 years, it is highly likely to diagnose benign prostatic hyperplasia, and these individuals are at a higher risk of prostate cancer compared to younger patients.

For this reason, prostate cancer screening is appropriate, especially if the patient displays symptoms, has a family history, or a recurrent concern about prostate cancer.

Alternatively, if it is a result of having more buildup of metabolic damage caused by having a longer time to make poor diet, lifestyle, or suffer adverse health events.

For more information on how to reduce your prostate cancer risk, click here.

Genetic

There are a few genes that are associated with an increased risk of developing prostate cancer.

These may explain why prostate cancer seems to run in some families. However, these genes are likely only to cause a small percentage of prostate cancer cases.

Inherited mutations of the BRCA2 gene can increase your risk of developing prostate cancer.

Men with the genetic condition Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), have an increased risk for a multitude of tumors, including prostate cancer.

The RNASEL mutation has also been linked to an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. Normally these gene works to lower your risk of cancer and suppress tumor growth.

However, inherited mutations in this gene seem to let cancerous and abnormal cells live longer than they should. This has been linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer.

The presence of a mutated HOXB13 gene is strongly linked to developing early-onset prostate cancer. This is probably because this gene plays an important role in the development of the prostate gland. While this mutation has been found to run in families, it is, fortunately, very rare.

Race

African Americans and Europeans of African or Caribean descent appear to have a far higher likelihood of developing prostate cancer than their white or Asian counterparts.

The higher risk seems to be entirely genetic though the exact genes responsible are not known.

According to the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), African-American men are approximately 1.6 times more likely to develop prostate cancer than Caucasian-Americans.

The greater likelihood of developing the disease is also matched by 2.4 times greater risk of dying from cancer than white Americans.

Though this number may be being affected by environmental factors, such as cost of treatment, dietary differences, and lower quality medical facilities in predominantly African American areas.

Diet and Lifestyle

There is an increasing body of evidence that diet and lifestyle play a critical role in mitigating prostate cancer risk. This is backed up by the massive difference in the rate of prostate cancer in Western Countries compared to Eastern ones like China, Thailand, and Japan.

There are a number of factors that we should consider.

Firstly, there is a chance that this disparity in prostate cancer rates is genetic. However, there are studies of migrant populations which show quite clear increases in certain diseases like prostate cancer, when ethnic Chinese move to western countries like America.

The change in prostate cancer and, in fact, in cancer risk rates, in general, seems to move with the generations of immigrants.

The first generation’s diet tends to remain fairly similar to what they ate before they emigrated. But, as each subsequent generation assimilates and their diet moves closer to the Standard American Diet (SAD), we see their risk of prostate cancer normalizing with the western average.

We can also rule out environmental factors such as pollution, as explanations of the east-west cancer divide.

A more significant difference is seen in highly urbanized Hong Kong, the rate for prostate cancer was approximately four times that in the rest of China – but still only around 8 men in 100,000.

The Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have rates of prostate cancer similar to those of Hong Kong. And, both cities were attacked with nuclear weapons. So, in addition to the usual pollution-related cancers, one would also expect to find some radiation-related cases of cancer.

It is fairly easy to hypothesize that the fourfold difference in Hong Kong is that Hong Kong is far wealthier and more westernized than the rest of China.

Their diet – especially that of successful and wealthy Hong Kong residents – includes the western quantities of protein, animal fats, and most important of all – dairy fats.

In fact, in China, the slang name for breast cancer in Chinese translates as ‘Rich Woman’s Disease’.

It is worth emphasizing that many Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan, are densely populated and have been highly industrialized and urbanized for many years, yet their rates of prostate cancer remain much lower than in the West.

The even more massive incidence is seen in the UK at around 40 per 100,000. And greater still is seen in the USA at about 110 per 100,000.

A full breakdown of the best anti-prostate cancer diet can be found in the latest edition of our guide to prostate health “All About The Prostate.”

Family History

The data suggest that prostate cancer runs in families, above we have already examined the genetic factors that can cause this.

However, there is probably an argument for some shared environmental considerations.

Whether or not that is a result of consumption of the same diet, and similarity of lifestyle, or an increased chance of shared exposure to carcinogenic substances is unclear.

What we can say for sure is that if your father or brother had or has prostate cancer, then you have twice the risk of the average man of developing prostate cancer in your lifetime.

The risk does not seem to change, for a father or brother. However, the risk is much higher if you have several relatives who had prostate cancer.

The age of your relatives also seems to be a factor. Your doctor or oncologist will take a full family history from you.

The age of your relatives when the tumor was first detected is relevant. The younger they were when the cancer was detected, the higher your likelihood of developing prostate cancer at some point in your life.

Despite there being an apparent genetic and familial risk factor, it is worth noting that most prostate cancers occur in men without a family history of it.

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia

A common precursor for prostate carcinoma is prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). This is a health problem known for epithelial cell growth. Since the PIN is a premalignant condition, it is also recognized as a sign of prostate cancer.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

The medical community is only now coming round to the conclusion that an enlarged prostate (BPH) is a risk factor for prostate cancer.

Medical orthodoxy can take time to change. However, the link is very clear when you examine the research.

There is certainly a strong link between BPH and prostate cancer.

A study at the Copenhagen University Hospital, Herlev, showed that men with BPH have an increased risk of developing and dying from prostate cancer.

The study found that over 27 years, BPH was associated with a two to three-fold increased risk of men developing prostate cancer and with a two to eight-fold increased risk of them dying from prostate cancer when compared to men that did not suffer from BPH.

Other research has reported contradictory findings.

For example, one study found men with smaller prostate sizes were less likely to develop prostate cancer and were less likely to develop aggressive prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer tends to develop in the peripheral zone of the prostate, while BPH usually occurs in the transition zone. Thus some scientists argue that there cannot be a direct link between the two conditions.

Men with BPH are more likely to be making regular visits to a urologist and undergoing prostate cancer screenings.

This may explain the link between BPH and prostate cancer. Family history is another strong risk factor that must be accounted for in research studies.

Can you feel if you have Prostate Cancer?

The short answer is no; you cannot feel if you have a tumor in the prostate. Prostate cancer, especially low-grade prostate cancer, is relatively asymptomatic. Some men live for decades with prostate cancer and never even know they have it.

While you cannot feel prostate cancer, your doctor may be able to detect it during your annual physical. After you reach 50 years old, your doctor may start including a digital rectal exam (DRE), into your routine checkups.

Your doctor will insert a finger into your anus and prod the prostate gland. They are feeling if there are any rough or hard nodules on the surface of the prostate that may indicate prostate cancer.

What’s new in Prostate Cancer diagnostics?

For the last few decades, the standard for diagnosing prostate cancer has been a Digital Rectal exam, into a PSA test, into a prostate biopsy.

However, in recent years, new diagnostic tests have been developed that work by examining other forms of PSA or other tumor markers.

Several of these newer tests appear to be more accurate than the older tests, including a PSA test.

We would still recommend a regular PSA test as part of your annual checkup.

PSA tests, along with rectal examination, may seem an old-fashioned method to detect prostate cancer, but it is still unbiased and reduces the incidence of false positives.

It is important to note that sometimes PSA would only show significant changes in cases of late-stage prostate cancer, which is why the traditional rectal examination is equally and sometimes more meaningful than most modern screening methods

If you are concerned about the possibility of having prostate cancer, you may want to talk to your urologist about getting one of the newer, non-invasive diagnostic tests done. These tests are:

- The phi test, which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, and pro-PSA to help determine how likely it is that a man has prostate cancer that might need treatment

- The 4Kscore test, which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and human kallikrein 2 (hK2), along with some other factors, to help determine how likely a man is to have prostate cancer that might need treatment

- The Advanced Prostate Health Assessment (APHA) is an online questionnaire based on the American urological society guidelines and international prostate symptom score system. It takes 5 minutes to complete the test, and while it is not a conclusive indicator of prostate cancer, it can be useful for calculating your level of risk.

- The Progensa test analyzes the level of prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) in the urine after a digital rectal exam (DRE). The higher the level, the more likely that prostate cancer is present. Again this test does not guarantee the presence of prostate cancer or give you any details about the type, size or aggression of the tumor you may have.

- A High-Resolution Color-Doppler Ultrasound scan. This is a new, more accurate scan that can see abnormal blood flow that may indicate the presence of a tumor; only some hospitals and clinics can perform as it requires specific technologies. It is a non-surgical and non-invasive diagnostic test.

These tests are useful, but you would probably only opt for them if you already suspect that your prostate health is degrading.

If you see no changes in your annual PSA test, then your doctor is unlikely to recommend any of these tests.

It is worth noting that there have been some new advancements in the color Doppler diagnostic that may result in it being even more accurate at detecting prostate cancer.

The latest techniques involve injecting the patient with a contrast agent containing microbubbles. This improves the clarity of the ultrasound images. However, very few hospitals are currently offering this test.

Are there any natural treatments that support prostate cancer?

Ultimately there are no “cures,” natural or otherwise, for prostate cancer.

There are certain treatments that can put it into remission, and there are others that can manage and slow the progression of prostate cancer.

The research is clear that for low-grade prostate cancers, there is no difference in longevity amongst patients that opted for treatment and those that opted for active surveillance.

Which, in the case of low-grade prostate cancer, may well be preferable to invasive treatment.

However, in the case of advanced prostate cancer or castrate-resistant prostate cancer (especially if it is metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer), you may wish to opt to for a more immediately to treat prostate cancer.

In cases of early prostate cancer and advanced prostate cancer, you may wish to consider making significant dietary and lifestyle changes for your health.

Some research shows that a high-fat diet, such as the ketogenic diet, may increase survival rates for prostate cancer.

Boron and Prostate Cancer

Research suggests that adequate boron levels may be associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer.

However, obtaining protective levels of boron from food alone is difficult.

Nutritional research shows that the western diet is low in boron. This suggests that supplementing with low-cost boron may potentially contribute to maintaining prostate health.

A 2001 study on the diet of prostate cancer patients that compared the diets of seventy-six prostate cancer patients with those of 7,651 men without prostate cancer.

The study found that the men who ingested the greatest amount of boron from their diets were 64% less likely to develop prostate cancer than those who consumed the least.

There have been further studies that have confirmed similar results. One such study compared the dietary intake of boron in ninety-five prostate cancer patients with that of 8,720 healthy male controls. That study was controlled for many other factors.

They too, found, that men with the highest boron consumption showed a 54% lower risk of prostate cancer compared to those with the lowest intake. This seems to confirm that a decrease in prostate cancer risk is directly proportional to the amount of boron that you consume.

Research has explored the impact of boron supplements on prostate cancer, showing potential effects on tumor size and prostate-specific antigen levels.

In an animal model, researchers orally administered various concentrations of a boron-containing solution to test subjects and found that this resulted in a decrease in prostate tumor size of 25% to 38%.

Remarkably, PSA levels dropped by an astounding 86% to 89% in the animals that received boron.

For additional information on the potential impact of Boron on prostate cancer, osteoporosis, and general health, please refer to this article.

Another natural nutrient that has been studied extensively in recent years is vitamin D. Research has found that high levels of vitamin D seem to lower your risk of developing certain, more aggressive types of prostate cancer.

Another 2012 study, that looked at the links between vitamin D and prostate cancer progression concluded that men with low-risk prostate cancer may benefit from Vitamin D3 supplementation.

In a year-long study where men with low-risk prostate cancer were given a year of vitamin D3 supplementation.

PSA serum levels were measured at entry and every 2 months for 1 yr. Biopsy procedures were performed before enrollment (for eligibility) and after 1 yr of supplementation.

In terms of safety, the study found no adverse events associated with vitamin D3 supplementation were observed. 55% of participants showed a decrease in the number of positive cores or a decrease in the Gleason score.

For more information on natural nutrients and their impact on both prostate and general health, click here.

What is Active Surveillance?

Active surveillance is used to monitor localized, early prostate cancer, instead of treating it straight away with surgery or radiotherapy.

It involves having regular tests to keep an eye on cancer through tests like MRIs, biopsies, or PSA tests.

Treatment is only opted for if the cancer prognosis changes or cancer spreads. This helps to avoid or at least delay the side effects associated with treatments.

Although some men worry about not having the treatment and their cancer spreading, many men can easily get on with their daily lives between check-ups without any noticeable changes to their day to day routine.

This is because low grade or early prostate cancer is largely asymptomatic.

Many of the men who opt for active surveillance will not need treatment during their lifetime.

Research shows that men who undergo active surveillance have the same chance of living for 10 years or longer as men who undergo radiotherapy or surgery, but with fewer and less intense side effects.

A different study found that all treatments had worse effects on a patient’s quality of life than active surveillance.

40% of men who had opted for Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) experienced some form of urinary leakage, as did; 33.9% of radiotherapy patients and 62% of radical prostatectomy.

However, only 12% of men who opted for active surveillance reported any urinary leakage, and this could largely be attributed to untreated BPH.

Another study by Punnen et al. showed that men who chose active surveillance were less likely to suffer from sexual dysfunction than men who underwent any form of prostate cancer treatment. Only 23% of the active surveillance group reported any sexual dysfunction.

Whereas the number of men reporting sexual dysfunction ranged from 38% to 68% in the various treatment groups.

Additionally, men who opted for active surveillance men also reported lower levels of urinary dysfunction than men who had undertaken a surgical treatment.

Another study conducted at 5 years after the initial treatment compared the effects of radical prostatectomy on active surveillance.

The study found that erectile dysfunction impacted 80% of the men that had undergone radical prostatectomy, but only 45% of men of the men undertaking active surveillance.

Also, a greater proportion of men who underwent radical prostatectomy suffered from urinary incontinence, with 49% of radical prostatectomy reporting urinary leakage compared to only 21% in the active surveillance group.

These studies show that overall active surveillance has fewer side effects than surgical and non-surgical treatments for prostate cancer.

Active surveillance has shown to have fewer side effects than both surgical and non-surgical treatments and is probably preferable whenever it is suitable.

Additionally, some studies suggest that the treatment options themselves do not necessarily elongate life expectancy.

These findings, combined with the severe nature of the side effects of the treatments, may explain the recent increase in the percentage of American men who opt for active surveillance.

RELATED: New Study Investigates Treatment-Associated Regrets In Prostate Cancer.

The best protocols for Active Surveillance

At the beginning of the active surveillance period, there are 5 separate, non-invasive tests that you may wish to get to give you the most accurate picture of the state of your prostate cancer. These tests are:

- Digital Rectal Exam.

- PSA test/ Free PSA test.

- Multiparametric MRI.

- Color Doppler Ultrasound.

You should do a full battery of tests at the beginning of the active surveillance to allow you to establish a baseline.

This should establish where the cancer is? How big is the tumor? How aggressive is the cancer?

All future tests are then measured against the original tests. This allows you to track the progression of the tumor, and decide if you ever need to opt for a treatment.

During the first year, you should take a PSA test every 4 months along with a Digital Rectal prostate exam. After 12 months, you should have another MRI and Color Doppler Ultrasound.

We would also recommend that you keep a daily prostate health diary. Which, is a journal of your symptoms, such as frequency of nighttime bathroom trips or urinary issues.

A sudden worsening of your symptoms can indicate a change in your prostate cancer.

From the second to the fourth year of active surveillance, you should have PSA tests every six months, and the scans every 12 months.

After you have been on active surveillance for more than five years, you can change to have a PSA test as part of your annual checkup and have the scans every other year.

Our Natural & Non-Invasive Prostate Biopsy Alternative

In our opinion, a far safer and gentler prostate biopsy alternative is our Advanced Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment (APCRA). This consists of non-invasive blood tests and specialized color Doppler scans.

The variety and sophistication of some of these new blood tests make this a very realistic alternative to a prostate biopsy, especially if you have a preference for non-invasive diagnostics and treatments.

After this testing, you will receive a thorough, 3-hour consultation from a Naturopathic Physician who is also a Professor of Urology and a very detailed, written report of your results to be discussed during the appointment.

He will walk you through the results of his assessment and explain every aspect and each option available to you, while also answering any questions that you may have. Your consultation will be like an educational mini-seminar about the real issues facing you as a patient.

Most urologists will have a preference for the particular treatment that they provide. However, the consultant you will see has no agenda and is completely free to offer honest, independent advice.

He will try and help with any information you need in order to arrive at your decision. But he will not try to sway you one way or the other.

Aside from that, the greatest additional benefits of the APCRA are that it is non-invasive, does no damage, and does not close off any avenues for future treatment.

To book our Advanced Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment please call our customer service team on +1-888-868-3554 who will be happy to assist you and offer any further information.

Can I survive Prostate Cancer?

The odds of surviving prostate cancer are quite good. However, this is mostly dependant on what type of prostate cancer you have.

If you are diagnosed with a slow-growing, low-grade, and localized prostate cancer, you will die of other natural causes long before your prostate cancer becomes a life-threatening issue.

Prostate cancer survival rates vary based on factors like metastasis and the aggressiveness of the cancer.

- Localized: The cancer is contained to the prostate gland, and there is no indication that it has spread. (This can include stage 1, 2, and some stage 3 cancers).

- Regional: cancer has spread outside the prostate to nearby organs or lymph nodes. (This mainly includes stage 3B and 4A cancers).

- Distant: cancer has spread to remote parts of the body, such as the lungs, bones, or liver. (This is usually staged 4B cancers).

For a breakdown and explanation of the stages of prostate cancer, click here.

If you have been diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, the numbers are reassuring.

The 5-year survival rate for localized or regional prostate cancer is 100%. Moreover, the 10-year survival rate for localized or regional prostate cancer is 98%.

However, despite these reassuring statistics and the research and progress that has been made over the last decade, prostate cancer is still the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States.

Approximately 88 men are killed by it every single day.

This is most evident when you look at the 5 survival rate for distant metastatic prostate cancer (prostate cancer that has spread to other organs, bones, or lymph nodes that are far from the prostate gland). The survival rate is only 30%.

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is a serious disease that affects men’s health, so it is very important to begin taking steps now to reduce your risk. The good news is that it is treatable.

Any man diagnosed with prostate cancer should be sure to seek information on possible treatments as well as a second or from professionals with no ties to the diagnosing clinician.

But do not delay in doing so because some forms of prostate cancer might be more aggressive than others.

Studies have shown that due to the usual slow progression of prostate cancer, time spent evaluating the conditions and treatment options does not interfere significantly with later treatment and overall prognosis.

Explore More